A Brief Overview: The UN vote on the WHO recommendations for the re-scheduling of cannabis

On the 2nd December 2020, at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in Vienna, Austria, countries will gather to decide on the fate of medical cannabis regulations around the world.

Dr Ayesha Mian | Centre for Medicinal Cannabis Advisory Committee & International Policy expert

On the 2nd December 2020, at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in Vienna, Austria, countries will gather to decide on the fate of medical cannabis regulations around the world. This comes almost 60 years after the creation of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, one of three international treaties that make up the international drug control system.

Following the first critical review of cannabis by the World Health Organisation, six main recommendations suggesting rescheduling of cannabis will be voted on by the sitting nations at the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs (based at the UNODC). If all of the recommendations were to pass, it would mean that cannabis will be recognised as having medicinal value and worthy of further scientific investigation.

On the surface, it seems there may be a chance for a global paradigm shift towards the legitimisation of the medicinal value of cannabis. However, politics and militant adherence to the status quo may cause further division, and disappointment, in the face of a rapidly growing medical cannabis industry, desperate for validation.

What is the international drug control system, what is this vote about and how will this vote make any difference, if at all, to the medical cannabis industry?

The International Drug Control system

A brief history on the legislation around cannabis

The cannabis plant has been used for thousands of years across the world for spiritual, medicinal, industrial and recreational purposes. It has a fascinating history, culture, and medicinal and scientific value that we have barely begun to unravel. Despite extensive research there have been a number of factors leading to its current -predominantly criminalised- status[1].

The 19th century saw a rising interest in the medical and recreational cannabis consumption among North American and European countries. It was listed in the British and American Pharmacopeias for its anticonvulsant and sedative properties as well as acknowledged by the American Medical Association, who also classified it as having low likelihood for addiction.

The development of the hypodermic syringe as a more reliable drug delivery system was among the many reasons why cannabis fell out of favour due to the emerging pharmaceuticalization of medicine. Several factors influenced its fall from use: first, its active constituents had not been isolated, the unreliability of tinctures and extracts and lastly, the fact that single component medications were developed covering medical cannabis' indications which in turn made them seem more reliable and effective.

Social use of cannabis became widely popular and was associated with lower socioeconomic backgrounds and minority migrants. Due to its incorporation into counter-culture identities there was a push for the criminalisation of specific populations through regulation. Numerous legal restrictions placed on the medical use of cannabis in America, such as the 1937 Marijuana tax act, which taxed medical use of cannabis, led to the prevention of further scientific investigation, an effective ban of cannabis and its removal from the American Pharmacopeia in 1941 (and from the British Pharmacopeia in 1932). Many countries across the world had their own complex histories with legislating for or against cannabis with Egypt being the first country to effectively ban cultivation.

The shifting power among nations following the two world wars amplified certain political agendas. A newly formed United Nations was utilised to solidify previous attempts at drug control into one single convention: The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

Countries that traditionally cultivated opium, coca and cannabis, predominantly Asia, Latin America and Africa, had their cultural practices effectively eliminated by the new Convention. This new regime would limit the production, supply and possession (in the context of supply) of specific ‘narcotic’ drugs, not including alcohol, to medical and scientific purposes. It is worth noting that the International Drug Control treaties did not control for industrial (fibre and seeds) use and did not cover personal possession. The goal was to eliminate opium, cannabis and coca within 25 years.

The international treaties

There are three key international treaties which form the legislative framework of global drug control : the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, as amended by the 1972 Protocol; the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971, and the Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988.

What do they control for?

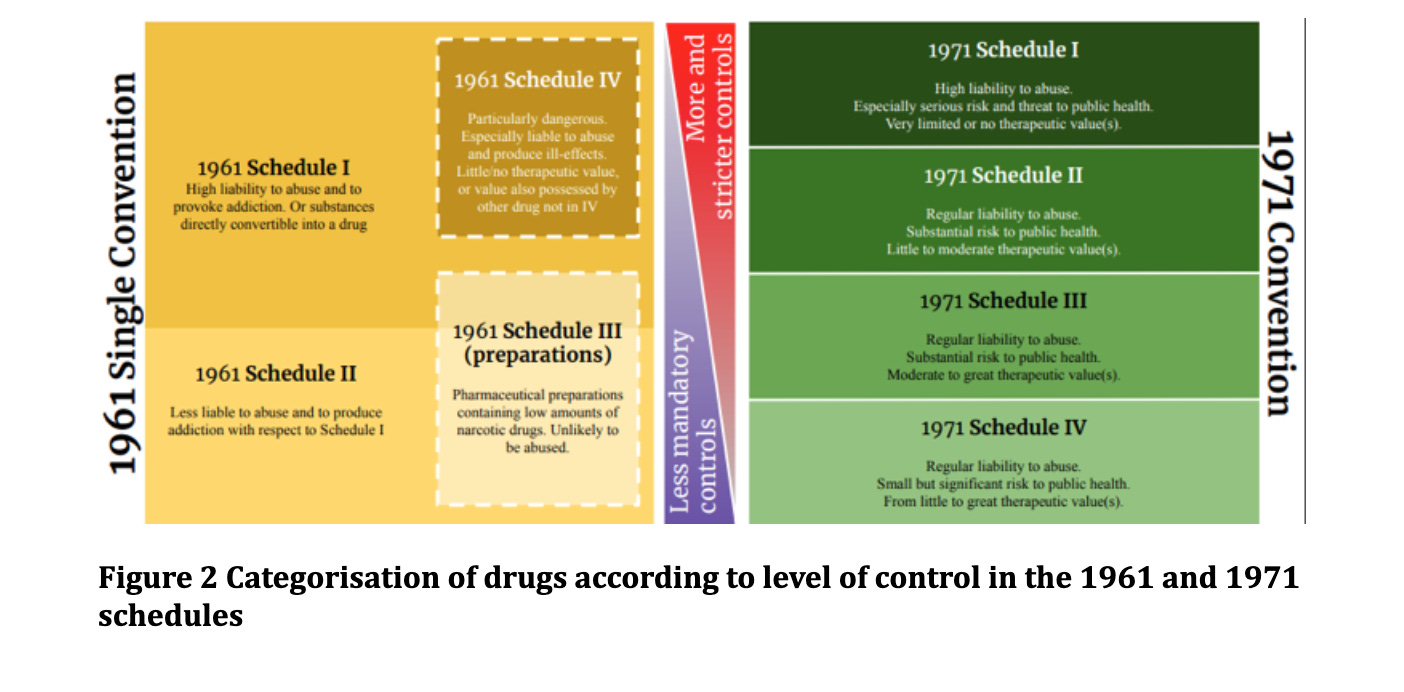

These international treaties have different categories, or schedules, with varying levels of control over the substances. Drugs were categorised based on medicinal value vs potential harms. This was to ensure availability for medical and scientific purposes and to divert away from illegal channels. They also control trafficking and production. The 1988 treaty has an annex listing a number of pre-precursor and precursor chemicals involved in the production of the scheduled drugs, thereby putting them under the strict control of the treaties for possession, production and trafficking.

What is the status of cannabis in the 1961 convention?

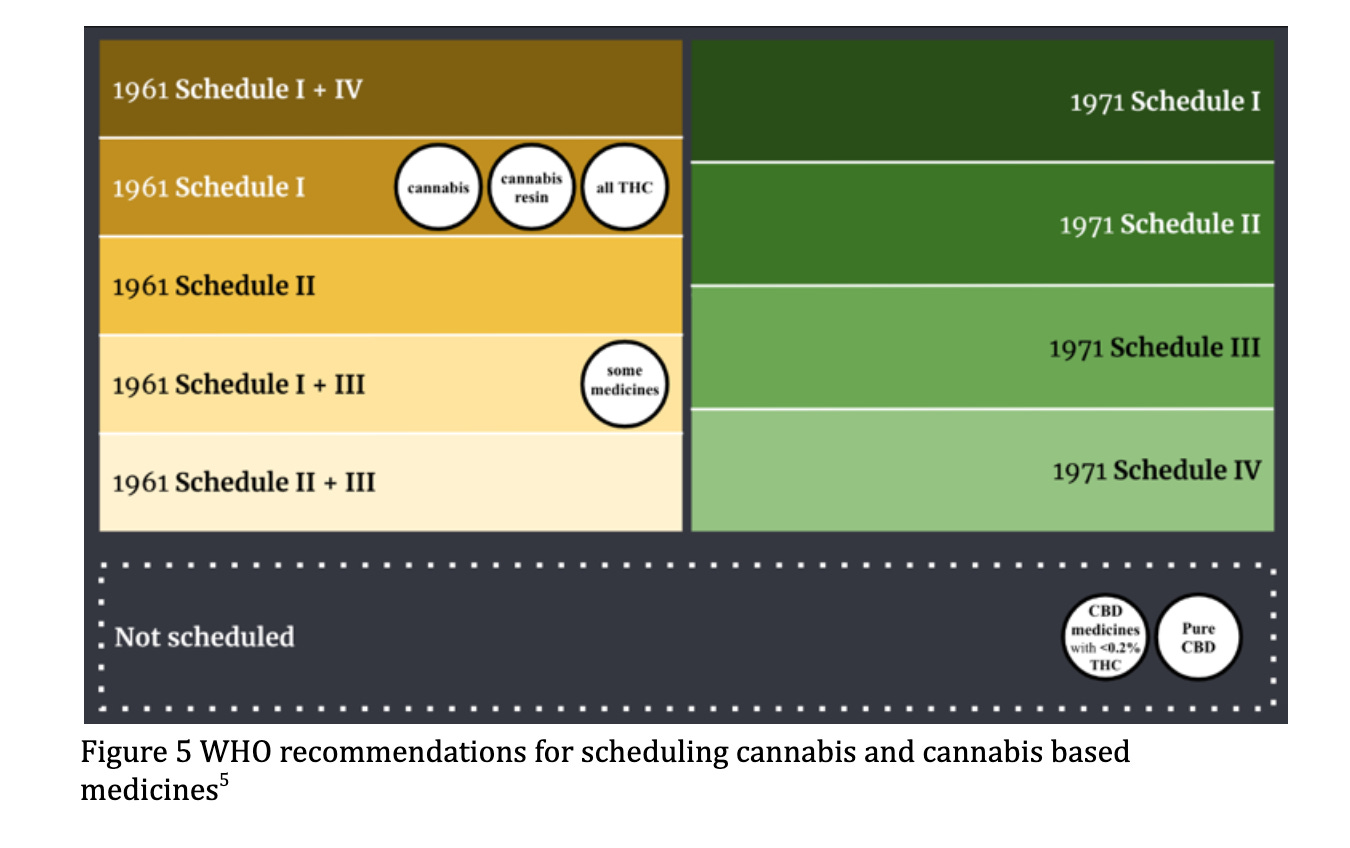

The Single Convention contains 4 schedules of classification of control for over 100 substances. The 1961 convention established a process for adding new substances without the need to modify the original text of the treaties. Schedule I and IV classify particularly dangerous drugs with high abuse and addiction potential. This is where cannabis and cannabis resin currently reside (see Figure 4).

What is the 1971 Convention about?

The 1960s brought about a new wave of emerging drug use. The strict control structure of the 1961 Convention faced criticism from the European pharmaceutical industry, seen as prohibitively restrictive over their free international trade. The 1971 Convention sought to respond to the diversification of drugs, including barbiturates, benzodiazepines, amphetamines and various psychoactive substances, with a less rigid control structure in comparison to the 1961 convention. This control structure contained four schedules with Schedule 1 being the most restrictive. Schedule 1 includes substances that pose a serious threat to public health, have limited or no therapeutic value and high potential for abuse. THC isomers and delta-9-THC (including dronabinol) are placed in Schedule 1 and 2 respectively.

The 3 UN bodies involved in maintenance of the treaties

The Commission on Narcotic Drugs, The international Narcotics Control Board, and the WHO each have specific mandates in relation to the treaties

CND

In 1946 the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)[3] established the CND as one of its technical commissions. At any one time, there are 53 member states that supervise how the treaties are applied as well as advising ECOSOC on matters relating to drug control. The CND acts as the enforcer of the treaties, ultimately deciding on the classification of drugs under international control. This should be based on recommendations made by WHO. The CND is not a group of experts, but government representatives who mainly act according to political interests.

The UK sits on the current rotation of the member nations voting at the UNCND.

INCB

The INCB is a monitoring body responsible for the implementation of the treaties. They include the regulation of the licit manufacturing, trading and use of drugs for medical and scientific use. The INCB monitors governments’ control over scheduled drugs in line with the treaties.

WHO

The treaties set out a specific function of the WHO: to assess the evidence for medicinal and public health properties of a substance, and recommend where the substance may be scheduled within the treaties[4]. The WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence reviews drugs up for classification, in turn advising the WHO Director General on what recommendations to make to the CND. There is a pre-review, which decides whether or not a critical review should be made. This is the first time in history that the WHO has taken an extensive critical review on cannabis. There was little to no evidence provided on the initial classification of cannabis, as it was automatically placed under control, along with coca and heroin.

What are the recommendations of the WHO?

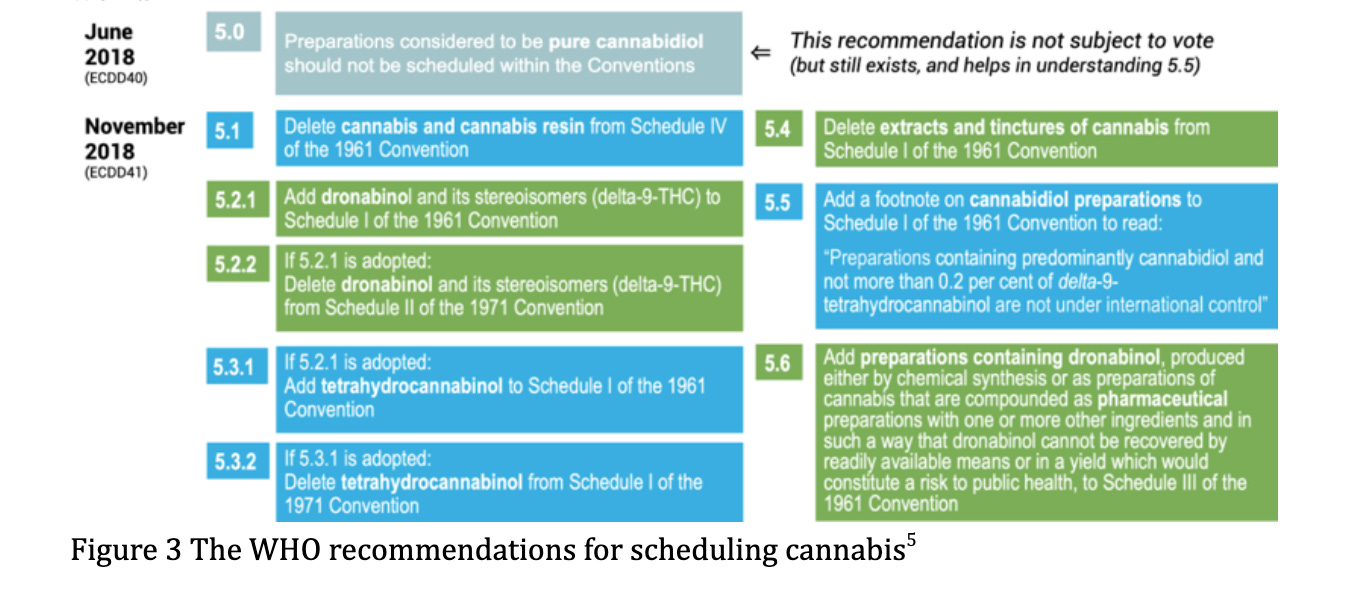

Following critical review of cannabis and cannabis related substances, the WHO director General made a series of recommendations in January 2019[5],[6] (see figure 1). They were presented in response to the increasing re-emergence of the therapeutic role for cannabis based medicines and subsequent legislative changes occurring throughout the world.

Under current controls, Cannabis, cannabis resin, extracts and tinctures, THC isomers, and delta-9 THC are within the most restrictive schedules of the 1961 and 1971 treaties, with little to no recognition of any therapeutic value. Of the recommendations made by the WHO, which will ultimately aim to ease restrictions on scientific research and acknowledge therapeutic value, recommendation 5.1 is most likely to achieve this outcome.

How will the countries vote?

Of the 53 member states, only 2 (South Africa and Switzerland) are anticipated to vote in favour of all the recommendations made by WHO. The remaining countries, except 9, of which the positions are unclear, are either partially or totally against all recommendations. The United Kingdom is likely to vote in favour of only one recommendation: 5.1, ‘Delete cannabis and cannabis resin from Schedule IV of the 1961 Convention’.

What are the implications of the vote?

If the recommendations, or even just recommendation 5.1 is adopted, it could embolden policy makers to pursue efforts to legislate for medical cannabis and allow countries to re-evaluate national control policies. If so, scientific research will face less of a deterrent and less costly restrictions.

Over time, many countries have deviated from the current strict control of the regimes, in particular for cannabis. With shifting global attitudes and legislation toward cannabis control, the current treaties seem to be less fit for purpose. However, there is still room for national policies to be improved and reduce the harms driven by current control efforts.

Unfortunately, it seems the recommendations of the WHO will not be voted in. However, it does not mean there is no hope! Many countries are now in direct violation of the treaties, in particular with cannabis. The rejection of WHO recommendations underscores the growing dissent in consensus around drug control[8]. Many national policies have been driven by public vote, based on the prevailing attitudes and advocacy of the people. Top down ‘control’ from the UN seems not to limit countries enacting national policy change.

As far as the UK is concerned, it is unlikely the vote will make much difference in the way it operates and there is a risk of further delay. If so, it could buy more time for countries to consider the evidence being presented. It may highlight that domestic interests and local pressures are more influential than the international treaties. Therefore, despite small, symbolic, changes at international level, national policy seems to be more significantly influenced by factors other than international drug control treaties. There is always scope for change and it’s up to us to determine how we make that happen.

Learn more about the scheduling system of the three international treaties with this short online course from the UNODC

A series of factsheets and articles outline the WHO process of reviewing the evidence around cannabis.

A website monitoring the positions of countries voting at the CND, and a short video with a great summary of the whole process. Keep informed of the process with live reporting from the CND blog.

[1] Collins, J. (2020). A Brief History of Cannabis and the Drug Conventions. AJIL Unbound,114, 279-284. doi:10.1017/aju.2020.55

[2] Cannabis medicines & WHO November 2020 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.26237.59363 Conference: International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines special 20th anniversary event

[3] “The Economic and Social Council is at the heart of the United Nations system to advance the three dimensions of sustainable development – economic, social and environmental. It is the central platform for …coordinating efforts to achieve internationally agreed goals. The UN Charter established ECOSOC in 1945 as one of the six main organs of the United Nations.” https://www.un.org/ecosoc/en/about-us, accessed 20/11/20

[4] For extensive set of factsheets and information on the WHO review process for cannabis see: https://www.researchgate.net/project/Cannabis-WHOs-scientific-assessment-of-medicines

[5] https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-and-policy-standards/controlled-substances/who-review-of-cannabis-and-cannabis-related-substances

[6] https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/ecdd-41-cannabis-recommendations

[7] https://kenzi.zemou.li/cndmonitor/

[8] Statement submitted from 193 NGOs across 52 countries which request the support of the UN to adopt the recommendations made by the WHO https://undocs.org/en/E/CN.7/2020/NGO/7